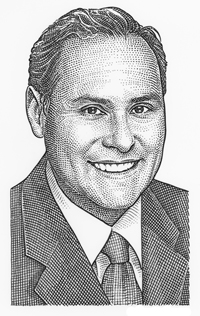

Fonts & Intellectual Property, an interview with Frank Martinez

By Jim Kidwell

By Jim Kidwell

Product Marketing Manager at Extensis

The issues surrounding copyright, intellectual property and design can confound even the most intrepid designer. Fortunately, there are those who specialize in the field.

One of those experts is Frank Martinez, the legal mind behind the intellectual property law firm The Martinez Group PLLC. Mr. Martinez’s work focuses on the legal issues surrounding the field of design, and this has often taken him into the legal and intellectual property issues surrounding the development, sale and use of fonts and typography.

Now considered one of the pre-eminent experts in the field, Mr. Martinez took a few minutes to answer a few questions about his design roots, font licensing and the future of design law.

JK: I understand that you have a background in design. What drew you to design as a career, and what was your focus?

FM: I studied art and design in high school and I have a BFA from Pratt Institute were I was a printmaking major. Once I started working and experimenting with fonts, I was hooked.

JK: How did you make the transition from design to the legal world?

FM: I knew from the first day of law school that I wanted to work in intellectual property. When I graduated from law school I spent 2 years at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office as a Design Patent Examiner. Within 6 months, I managed to become the Examiner responsible for issuing design patents for font designs. Within a year, I started contributing articles to ID and Print Magazines about issues relating to design and the law. By and large, most of my articles were about fonts, protecting fonts and protecting creativity. Since I went into private practice, it’s been all fonts, all the time.

JK: What would you say makes the legal issues surrounding the design community unique?

FM: In a nutshell, there are four primary issues. First, in the United States art and design has always been the handmaiden of commerce. It is hard to get business owners to understand that good design is art and to quote Milton Glaser, Art is Work. It is the erroneous perception in the business community that making art is an escape from a responsible adulthood that underpins the general lack of appreciation for the work of designers and an understanding of the intrinsic value of good design.

Second, as a general matter, designers and artists are not particularly astute business owners. Because there is no exposure to basic business and legal studies as a part of professional design education, designers are, for the most part, unable to authoritatively provide justification for the difficulty of the creative process and value of their work. In addition, designers do not have the tools to understand the legal framework that is used to protect their work.

Third, the mechanisms for protecting creative work are fragmented and unnecessarily confusing because different creative endeavors are protectable by different bodies of law. Artworks that have any usefulness are considered “utilitarian” and cannot be protected by copyright law. If you create a set of sculptural lampshades, you cannot copyright them. But non-illuminated sculptures bearing the identical form could be copyrighted. If you design a website, you cannot protect it by copyright since the Copyright Office views the attempt to copyright “graphic design” as an attempt to claim ownership of points or coordinates on a two dimensional grid. However, a claim to a copyright of the compilation of those images and text comprising the very same website can be copyrighted. Type font designs are expressly denied protection under copyright law in an effort to make sure that no one can claim “ownership to the alphabet.” However, the software creating the font can be copyrighted. Irrespective of their creative and artistic content, logos are considered trademarks and can only be protected by trademark registration.

Finally, it can be expensive to protect design works. Enforcement of rights by litigation or providing a plausible threat of a lawsuit to protect design is daunting, complex and expensive. Most corporate infringers can fund stiff and expensive-to-counter defenses. If a designer doesn’t protect their work product by solid contracts and, where appropriate, copyright filings, it will be hard to find an attorney willing to represent them. Copyright law provides incentives to register, among them the ability to claim enhanced damages as well a right to seek costs and attorney’s fees from an infringer.

JK: Staying legal is a job for both those who design typefaces and those who use them. What can you recommend as best practices for each group?

FM: Keeping it simple, conduct an audit; know what fonts you have and make sure that you have a license for the number of users and the methods of use. A good place to start to understand whether you are properly licensed is to read the EULA and if you can’t find one, go online to the foundry website. If you are not sure whether your use and/or usage are licensed, call the foundry. Trust me, they will be very, very happy to speak with you and will probably extend a discount, just because you called.

JK: Do you have any tips for those who are reviewing font EULAs to determine appropriate use?

FM: Most current EULA are pretty explicit as to what is allowed and prohibited. If the EULA you are reviewing is not, seeking to exploit perceived loopholes in the EULA will eventually cause a dispute. Again, if you are not sure, call the foundry.

JK: Can you recommend when it’s a good idea to consider legal counsel for font issues?

FM: If you are a foundry; as soon as reasonably possible. If you are a designer or the client of a designer and you believe that there may be a font use or license issue, sooner than later. Font designers will eventually find unlicensed or improperly licensed uses. If you are a designer and you need to purchase a font license, make sure that your use and your client’s uses are adequately licensed. If your client will need the font, make sure your client is also licensed.

JK: Fonts can be easily copied from one machine to another, and even easily downloaded from the Internet. This has lead many to treat fonts as “free.” What would you say to help convince people to better monitor their use of fonts?

FM: Font foundries are usually small businesses. It can take thousands of hours to design and implement a good font family. Using unlicensed fonts is no different from stealing from the corner mom and pop store. Proper licensing will result in a richer selection of fonts and better fonts because foundries will be incentivized to create products that the market will license. Finally, if you are designer, be self-interested, it is a lot less expensive to purchase a license than to lose a client and fight a lawsuit.

Read the complete, unedited interview on the Extensis blog.